Reading was an essential part of my growing up. My parents were both teachers and voracious readers. During the summer we went as a family to the library at least once a week. Wherever we were, Brooklyn, Champaign-Urbana, Worcester, we frequented the library. I remember particularly loving biographies. I believe there was a series specifically for children and I read them all. I was inspired by the stories of Frederick Douglass and Harriet Tubman, drawn to stories of heroes who overcame fear and danger to find freedom. Though my life bore no similarity to them, I wanted to be heroic. I wanted to be part of the fight for freedom and justice.

As I think about it now, there were a number of strands that came together to fuel this passion. I was aware that my paternal grandfather had lost his parents and sister in the Holocaust. My grandfather, Leo, came to this country alone when he was 17, in 1921. He had a cousin here, but left his family behind in Austria. I think he immigrated with the assumption that at some point the rest of the family would join him. He married and established a life for himself in New York. During World War II he received a letter written by a priest from his hometown informing him that the Nazis executed his family. This was not spoken of in the family, it was simply too painful for my grandfather.

I was also aware of the larger story of the Holocaust. I don’t know how old I was when I learned about it; it seems to have been part of my entire conscious life. Between that, the protests against the Vietnam War and the civil rights movement, I was preoccupied with the injustices in the world. I turned to books to try to find hope and maybe answers.

As I got a little older, I moved beyond those simple biographies. I was in the sixth grade when my oldest brother, who was in high school, was reading Down These Mean Streets, a raw and graphic memoir by Piri Thomas about growing up in Spanish Harlem. I picked it up, I was shocked and fascinated by the sex, drug use and violence and I couldn’t put the book down. It gave a glimpse into a life that was foreign to me. I was acutely aware that I was living in the same city as Piri Thomas, but leading such a different life. I tried to understand how our worlds could coexist.

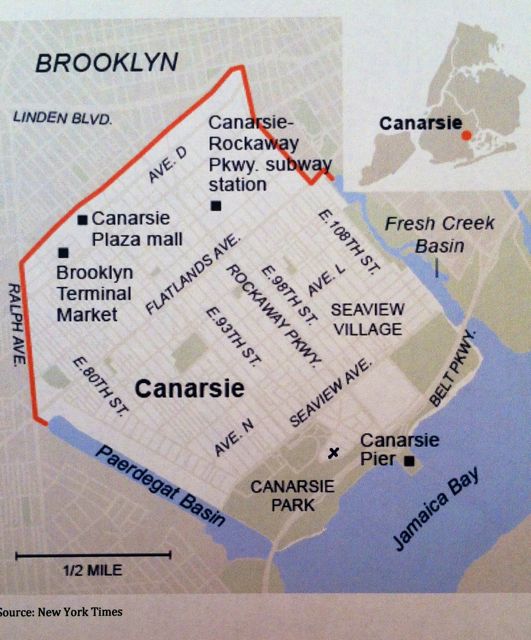

I knew that Canarsie sat next to a really dangerous neighborhood, East New York. One of the ways to get to the city from Canarsie was to take the LL (now called the L) train. The LL traveled through that neighborhood above ground so you could see the pigeons perched on the fire escapes of the tenements that abutted the subway line. I would watch the subway doors open and look at the people who got on the train from those stations. I wondered how it was for them to live in a neighborhood with so much crime and poverty. Here we were, side by side in one sense, but living in such different worlds.

One time I got on the LL to go to downtown Brooklyn to apply for my learner’s permit. There was only one DMV office to service all of Brooklyn and the DMV was spectacularly inefficient so you had to plan to spend hours there. After I got on the train, I realized I had forgotten my birth certificate. I was too afraid to get off the train at any of the stops until Broadway Junction where I would normally get off to change trains anyway. I wouldn’t turn around at 105th St., New Lots, Livonia, Sutter or Atlantic Avenues. Each time the subway stopped and the doors opened, I looked at the platform and thought, “Should I risk it?” Each time I decided I wouldn’t.

Another time I was riding the LL in mid afternoon when there was an announcement over the PA. Those announcements were usually so garbled and static-y as to be indecipherable, but this one came through quite clearly. “Move away from the windows! There are reports of gunfire. Move away from the windows!” There weren’t very many of us on the train at the time. Most of the people looked incredulous, a few moved to the windows to see! Some ignored the message entirely. I shifted down on the bench so the wall of the subway car was behind my head. Fortunately nothing happened – at least not in the car I was riding in.

It is amazing to me that some of the areas served by the LL have become hot real estate today. Some of the neighborhoods have gentrified, unfortunately I think the poverty has just moved. Still people live side by side, riding the L, the haves and the have-nots. I’m still reading, trying to understand.