A brief aside before continuing with my stories:

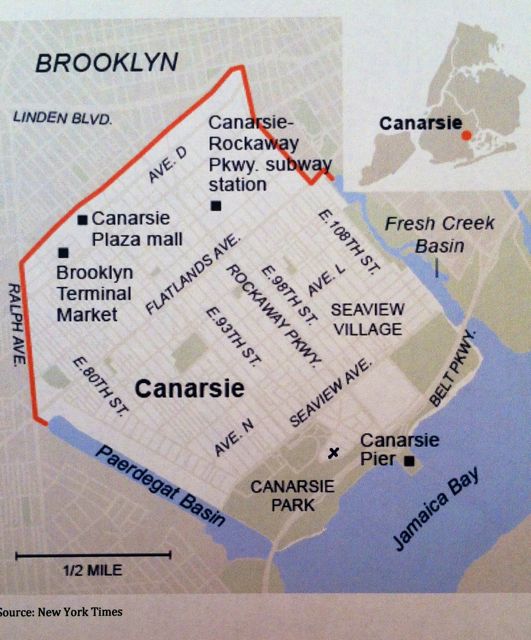

In order to better understand some of the events I’m describing, especially for those not familiar with Canarsie, I thought a map might be helpful. The small ‘x’ at the bottom is where my family lived – the small enclave jutting into Canarsie Park. When I was growing up we called it Seaview Park. This map shows that the park abutted the Belt Parkway. While it may have been parkland when I was growing up, it wasn’t in anyway improved, there were no ball fields or playgrounds; it was simply ‘the weeds.’ Now back to the story…..

_________________________________________________________________

The general zeitgeist of the ’60s, and the sights and sounds unique to my neighborhood made for a childhood woven with strands of anxiety.

If you were a girl growing up in the late ‘60s in New York City then you grew up in the shadow of the murder of Kitty Genovese. Perhaps not everyone was as affected as I was, but that story of neighborly indifference, of violence, of the callousness and danger of living in New York City, was part of the air that I breathed. I now know that the story is far more complicated than originally reported; there weren’t as many witnesses as the newspapers said at the time, calls to the police were made and a bystander did actually help her. But, that wasn’t the story that was embedded in my psyche at the time.

Kitty Genovese was murdered in Kew Gardens, Queens in March of 1964. The legacy of that crime was that we believed that people in New York City wouldn’t get involved, that New Yorkers took minding their own business to a dangerous extreme. Coupled with the incredibly high crime rate, this made for a fear of potential victimization and perhaps it became a self-fulfilling prophecy; a story we told ourselves.

I never liked when my parents went out for the evening, unless Nana and Zada were home. I would hear creaking, rustling and other assorted sounds – the usual sounds a house makes – and I imagined someone was trying to break in. It was hard to distract myself though I tried by watching television with the volume turned up. Of course some of the television shows of that era, Hawaii Five-O, Mannix, Twilight Zone, played on those story lines. My brothers weren’t helpful in comforting me. I likely didn’t share my fears since Mark in particular would look for any and every opportunity to tease me.

It was a time when once it got dark, we stayed inside. For as long as we lived in Canarsie, if an event or activity was going to end after dark, I had to have a specific plan for getting back to my front door. Since we had only one car this often meant that my father drove far and wide to pick me up. Fortunately, he did this with good humor and generosity. I’m pretty sure those limitations didn’t apply to my brothers.

The feeling of menace was heightened by our surroundings. With the park on one side and “the weeds” on the other, it was easy to imagine sinister people lurking. “The weeds” were the marshy landfill that separated our block from the Belt Parkway. When I played with Susan, one of my two friends in the neighborhood, we would ride our bikes on the street that ran along side the weeds. We would dare each other to run in and run out, not a dare I was willing to risk.

Our neighborhood was also in the flight path to JFK. Airplanes would skim over our roof. If you were on the telephone you had to pause in your conversation because there was no chance of hearing or being heard. If you were watching TV you had to hope you didn’t miss a crucial piece of dialogue. If any of our cousins slept over, the roar of the jet engines took some getting used to. My cousin Ahri, who grew up in Manhattan (not exactly a bastion of quietude), asked me how I could stand it.

If the wind was right, coming from the southeast, it brought with it the smell of one of the city dumps. One might imagine it carrying the smell of the ocean, since we were so close to it, and it did that, too. But, the dump was located along side the Belt Parkway, just past our exit and the odors emanating from it trumped the fresh smell of sea air. The mounds of trash rose like a small mountain range on the south side of the Parkway. Naturally I had a sensitive nose.

The dump also attracted scores of seagulls. The detritus and Jamaica Bay beyond were quite an attraction for all kinds of birds. The cries of the gulls were another constant part of the soundscape of our Canarsie neighborhood.

There was a fine line between the pleasures of the park, the beauty of the gliding gulls, the earthy smell of the marshes and ocean air, and the menace those same features held. All the elements, sights, sounds and smells, would often conspire to heighten a sense of foreboding, at least in my imagination.