Note: One of the reasons I started writing these memoir-stories was to explore different aspects of identity. I have struggled with notions of femininity and masculinity, as well as issues of social justice with respect to race and class for as long as I can remember. Some of the stories I have posted have touched on these topics. The essay that follows is intended to be one of several on race and ethnicity – it is a big topic! And, I have a couple of experiences I want to share. I welcome your contributions to the conversation – please feel free to share your perspective by commenting or sending an email.

“What are you?”

When I was growing up in Brooklyn in the late 60s, it was one of the first things we asked each other. It was a way of sorting ourselves out. I wonder if kids still ask each other that. As adults we tiptoe around those questions.

When we asked, in that place and time, we were usually asking whether the other person was Jewish, Italian-Catholic or Irish-Catholic. There really weren’t that many other possibilities in my neighborhood. I’m embarrassed to say that I was a young adult before I realized that there were many other possibilities – and how small a minority I was part of.

I’m not writing nostalgically of that time – I don’t think those were the good old days. I have been reflecting on why we asked each other that question and what it meant. I think we need to figure out how to talk about our identities in a way that doesn’t stir up suspicion, insinuate judgment or assume superiority. We are, after all, curious about each other.

As kids we were figuring out our identities and where we fit in. In asking the question ‘what are you?’ it felt to me like we were looking for connection, searching for commonality. The question was a shortcut to understanding something about each other and the answer could help seal a bond. And if it didn’t create a bond, it gave a point of reference.

We talk about prejudice being learned and in part I think that is true. Certainly we don’t come into this world thinking that a particular group is cheap or dirty or dangerous. All of that is learned. But, I think there is a hard-wired discomfort or suspicion of those who are different from us and that makes fertile ground for prejudice. We are born into a family or culture that defines what is comfortable and known to us.

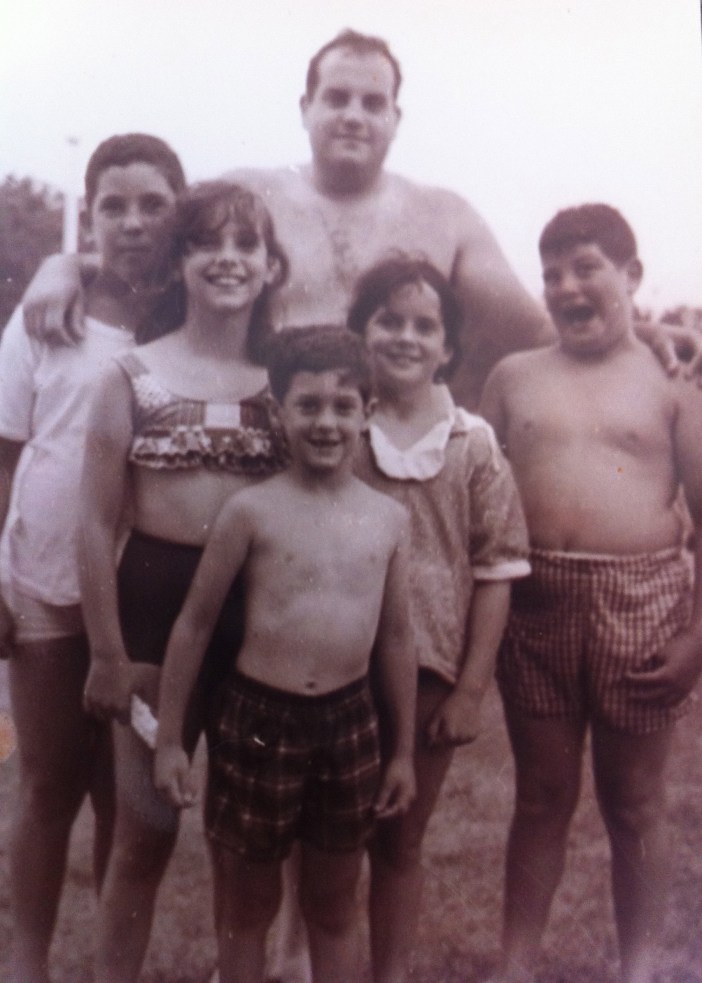

I was born into a second-generation Jewish-American family. Actually both of my grandmothers were American born, which would make me third generation, and my grandmothers were high school educated. Both of these facts made my family a bit unusual in my neighborhood. My parents were not only college graduates, but my Dad had one master’s degree in education and another in economics. My mom was going back to school while I was growing up and earned her master’s in reading. Education was a value in and of itself.

We took great pride in being Jewish, though we weren’t religious at all. I recall Nana lighting Shabbos candles on Friday nights. I have a mental picture of her moving her hands forward and back over the candles as if to invite the flame into her heart, her white hair covered by a white doily. Then she put her hands over her eyes as she completed the prayer silently. That was the extent of our ritual. We didn’t go to synagogue and we enjoyed ham, among other treyf (unkosher) items. Judaism was a culture to me, a sense of humor, and a way of looking at the world. It meant asking questions. It included certain foods at certain times of the year. It didn’t include God.

I was and am ethnically Jewish. My grandparents liberally sprinkled Yiddish in their speech. Shana madela (pretty girl), lay keppe (lay your head down), meshuganah (crazy), and schnorer (a moocher) and many other words were part of our lexicon.

One Yiddish word confused me. I grew up hearing blacks referred to as “schvartzes” by my grandparent’s generation. It wasn’t the equivalent of using the n-word, but it was a pejorative. When I sat at Nana’s kitchen table listening to her conversation with friends and family and the word was used, it sounded wrong to my ears, it was a discordant note. When I was older Aunt Simma shared a story of being told that she couldn’t go to a black classmate’s house to play when she was a child, though she was welcome to invite the girl to her own home.

I never had to face that issue, though I can’t imagine my parents issuing such an edict. There weren’t any black families on my block. There were only one or two black kids in my elementary school classes and neither of them were girls. Even in high school, my life was pretty segregated. My path crossed with black kids in gym and on the basketball team. The relationships didn’t extend beyond the court.

I’m 56 years old and still trying to sort out the different aspects of my identity and what it means for my relationships with family, friends and the larger community. In some ways it has gotten even harder to talk about.