Note: First, today, September 3, 2018, is Paula and David’s 68th wedding anniversary. Theirs has been an extraordinary journey and I hope today’s post does justice to part of it. I wish them the happiest of days together and I thank them for all that they have given us.

One of the difficulties inherent in working from Paula’s recorded oral testimony is deciphering the names of people and places since they are either Yiddish or Polish. I have done my best to present the correct names and locations, but acknowledge that it is unlikely that I have captured all of it accurately. If any family members have information to share, please do! I don’t believe those potential inaccuracies change the meaning of the events described.

This week I pick up Paula’s narrative after a father and son came to Serniki with the terrible story of the mass murder of Jews in a town to the west.

After the two men shared their story, the atmosphere in Serniki changed, even if many didn’t believe the details. The townspeople knew the Germans were on their way. The Russians retreated, leaving a power vacuum. While some may have been hopeful that the Germans would represent an improvement over the Communists in terms of business climate, there was trepidation and uncertainty about what the future held.

Many Jews decided to hide their valuables, believing that they were vulnerable not only when the Germans invaded, but at the hands of their Gentile neighbors. Some Gentiles took advantage of the power vacuum and appointed themselves police and meted out justice as they saw fit. Jewish homes were robbed, violence against Jews was perpetrated without consequence.

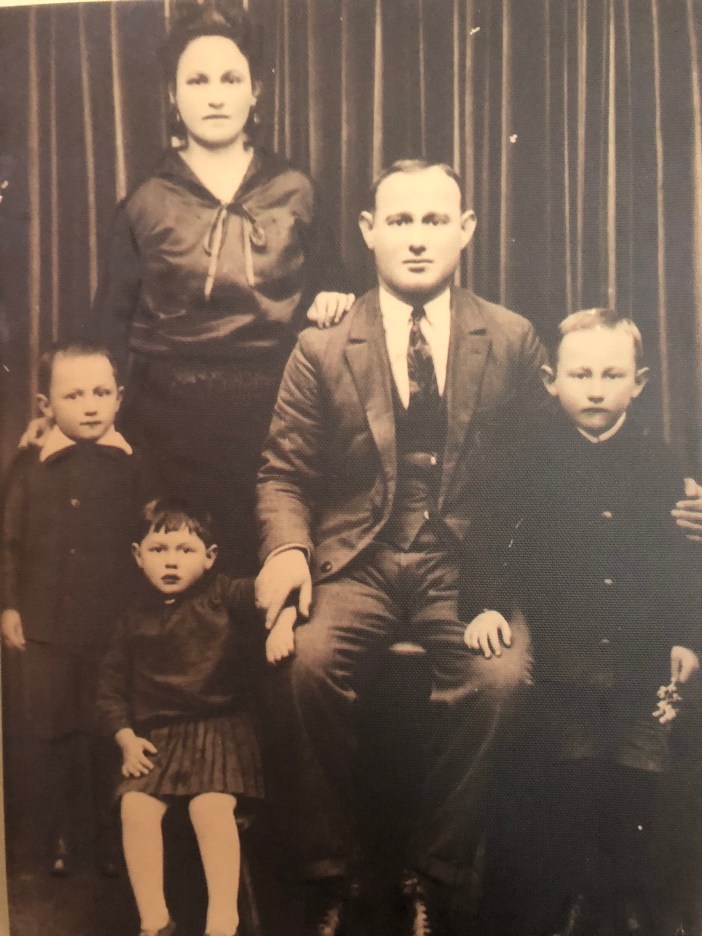

It was July of 1941 and the atmosphere in Serniki was getting more tense by the day. The Silberfarbs took their valuables to a farmer, who did business with Samuel, for safekeeping. The whole family went to the farmer and they were thinking of continuing on to leave town permanently. Before they could do that, they received word that Gershon (Paula’s paternal grandfather) had been murdered. They went back to Serniki to bury him.

A man named Danilo Polohowicz (Paula didn’t spell the name, so this was my best attempt to decipher it) was identified as the murderer. According to what the family heard, Danilo simply shot Gershon as he stood in his backyard garden in broad daylight. There were witnesses. Danilo wasn’t arrested or prosecuted for the crime.

Note: In doing research about Serniki, I found information about the trial of a war criminal in Australia. A man named Ivan Polyukhovich, who was from Serniki and was alleged to have participated in the mass murder of Jews there, had resettled after the war in Adelaide, Australia. He was tried for war crimes there in 1990. The last name seemed similar to the one Paula identified. Ivan Polyukhovich had 6 siblings. Perhaps, one of those siblings was responsible for the murder of Gershon Silberfarb, but this is conjecture on my part. Ivan was acquitted in 1990 of the war crimes because of lack of evidence and lack of eyewitness testimony.

The Silberfarbs were now back in Serniki to arrange the funeral and sit shiva for Gershon. The Germans had still not arrived, but with the knowledge that they were on their way, and with the Gentile townspeople turning on their Jewish neighbors, it was a dangerous and tense time.

Samuel went to his father’s house to oversee the funeral arrangements and ended up staying there to rest. Lea and the children went back to their house, but instead of staying in the main house, they spent the night in the apartment next door. Lea thought, given the atmosphere in town, that the house would have been a more likely target of robbers. In fact, the house was robbed that night. The four Silberfarbs, Lea and her three children, huddled under the bed in the apartment, listening to the sounds of people breaking in next door. The next day they found the house in disarray, with the floorboards lifted. Apparently, the thieves were looking for hidden valuables.

The next day a German soldier on horseback came through the streets shouting, “Every Jew to the market!” Lea knew what that meant. She had no intention of taking her children to the market. Samuel still wasn’t home with them – as far as they knew he was still at his father’s house (or his Aunt Fanny’s house nearby), both houses were near the market, or he may have already been killed. Lea decided to try to escape with the children. She didn’t know what happened to Samuel, but she didn’t think she could do anything to help him so she turned her attention to saving her children.

They ran out their backyard through fields, across roads, towards the Stubla River. Bernie abruptly stopped, before they got to the river. Lea had initially persuaded him to come, despite his reluctance to leave without his father. Now Bernie was unwilling to go any further – he said he wouldn’t leave without Daddy. Lea couldn’t convince him. Bernie turned back and went to the market. Lea felt she had no choice but to continue. She took the girls to the farmer who hid their belongings. When they got to his house, he covered them with hay and told them to wait. He went to town to investigate.

The farmer came back and reported that the Germans kept the men to do work – to dig ditches. The streets of Sernicki flooded easily and in preparation for trucks and troops, they commanded the Jewish men of the town to dig drainage ditches. The women and children were sent home. The farmer told the Silberfarbs to go home, they would be safe. Instead of going home, though, they went to a cousin’s house. This cousin’s house was situated closer to the Stubla and offered a better route of escape (from their own house they had to go through Gentile parts of town to get to the river). By this time, it was dark out. They were relieved to see a light was on in their cousin’s house– if the house was dark, Lea was prepared to hide under the bridge by the river. They were doubly relieved to find that Bernie was also there. He had gone to the market, but since he was under 14 years of age, too young to be put to work, he was sent home. He, too, decided to go to the cousin’s house. Bernie reported that he hadn’t seen his father.

The next day, Lea went to the market alone to see if she could find Samuel. Instead she saw her nephew on a work detail. While she was near the market a Gentile townsperson gave Lea a message from her husband, “Say kaddish for me.” [Kaddish is the Jewish prayer for the dead.] Lea couldn’t allow herself to panic or be distracted. She went back to the cousin’s house and thought about what to do next.

That afternoon they heard machine gun fire. Later they heard what happened to Samuel. He was hiding in the garden of his Aunt Fanny’s house with his uncle, Avrumchik. They discussed escaping. Avrumchik agreed to run to the river first because he wasn’t married and he had no children. If there was no gunfire, Samuel would follow. There was gunfire, but unbeknownst to Samuel, Avrumchik wasn’t injured. Samuel stayed put. The German soldiers, combing the town for Jews, eventually found him in the garden and shot him.

That day 120 men, the town’s Jewish leaders, and one woman were executed. The Germans did not liquidate Serniki at that point. They created a ghetto for the remaining Jews. Families doubled up in houses located on just a few streets. The Silberfarbs lived in the ghetto with another family for a year. Uncle Avrumchik looked after them.

While living in the ghetto, Paula learned to knit and crochet (which turned out to be valuable skills). Fortunately, they had books – Paula remembered sitting by the window reading by the moonlight reflecting off the snow. Food was scarce – mother would make a soup with a few potatoes, mostly water. They were barely getting by and, in fact, Lea’s mother passed away while they were in the ghetto.

Lea knew that they would not be permitted to stay in the ghetto indefinitely. The Silberfarbs snuck out and went again to the cousin’s house closer to the river. Across the Stubla there was a small group of wealthier homes (some Jews lived there – Paula thought perhaps they were allowed to stay by paying bribes). Those homes provided an even better opportunity for escape. The Silberfarbs had a relative in one of those homes – they decided to try to get there. Though there was a guard at the bridge, they studied his routine and Bernie and an Aunt and Uncle managed to sneak across. Lea and the girls planned to go the next day. During that time, there was a call for Jews to re-register. Lea understood what this meant and told her children “We are not going! We will not go back to town.” Uncle Avrumchik did go back to investigate (they never saw him again). That night Lea couldn’t sleep. She sat in the window looking out. She saw headlights coming across the bridge– she understood that this meant that more of the German army was arriving. Lea woke everyone in the house (more than just the Silberfarbs were there) – they went out the back and fled across the river and into the woods. They dispersed in different directions, though Lea, Paula and Sofia stayed together. The next day they heard the rat-a-tat-tat of machine gun fire coming from town.

Lea thought of a man that Samuel used to do business with – they would try to make their way to him. His name was Dmitrov Lacunyetz (??). They made it to him – he cried like a baby when he saw them and heard what happened to Samuel. Bernie, and the aunt and uncle had already arrived at Dmitrov’s farm. Dmitrov brought them to a forested area on his property to hide. He kept them there for 16 weeks, during which time the Serniki ghetto was liquidated. 850 Jews were murdered.

Dmitrov brought them food once a day. After a while, he sent his son-in-law to deliver the supplies. In order to avoid bringing suspicion upon themselves, they varied the routine. The son-in-law, now that it was getting colder, built them a little hut out of young birch trees. There were 8 of them in hiding. They had two spoons. Two people at a time would eat from the kettle that was brought to them. There would be some arguing over the food – “Don’t eat so much! Leave for the others!” It was usually a soup with millet (a grain used frequently in the region). At one point, Bernie was so hungry he couldn’t take it anymore – he went begging. He had some success and brought back and shared whatever he was given. On his rounds, he was asked “Are you Gypsy or Jew?” He said, “Gypsy.”

There was a Partisan brigade in the area that was in touch with the Russian government. Though they weren’t part of the brigade, Lea felt they were safer when they were near the Partisans. Throughout the war, she moved her family according to where Partisans were active. This particular brigade was made up of Jews, Russians and other Gentiles. Unfortunately, there was an incident involving a farmer where, in a dispute over a cow, the Partisans killed the farmer’s son. The farmer vowed to call the Germans. The area became unsafe. It was now the end of 1942. The Silberfarbs had to move on.

They met up with another group of Jewish people in the forest who knew where there were other Partisans. The group stayed hidden in the woods as they traveled. Lea would venture out and knock on doors at night to beg for food – many gave; others didn’t. One night a dog caught her by the foot and the wound became infected. According to Paula, Lea boiled young pinecones and used the water to disinfect the wound.

People in the woods would scatter when it became unsafe. At one point, while Leah was hobbled by her foot injury, Bernie left them, he was angry at his mother’s perceived weakness, and went ahead. After a while, he came back – he couldn’t leave his mother and sisters. Eventually Lea’s wound healed.

Another farmer took them to a hut. Lea sewed for that farmer and they provided food in return. They stayed for about 6 weeks. During this period of relative stability, Paula noticed the beauty of the green forest that surrounded them. To Paula the woods came to represent safety.

At the end of the 6 weeks, the farmer told them where there was a Jewish encampment and they started in that direction. But then they heard shooting, so they changed direction. Apparently the Partisans there got overconfident, got drunk and another group came (Crimeans?) and attacked them. Jews and Partisans were killed. Fortunately, the Silberfarbs weren’t among them.

Again in the forest, a man on a horse, Natan Bobrov, who was from Serniki, found them. He told them that more Jewish Partisans were in Lasitsk, a town north and east of where they were at that point. They made their way there.

During all of this, Lea fed her children positive thoughts. “The war will finish,” she reassured them. She reminded them, “We have family in Brazil and Cuba.” She kept their spirits up as best she could. She was always thinking a step ahead, of ways to escape. “We had hope,” explained Paula. They huddled together for warmth and kept going.

They came to another house where they were allowed to stay. Paula was asked to crochet a huge scarf with scalloped edges– she didn’t actually know how to make it, but she figured it out. Paula stayed in the house, she knit or crocheted all day, making gloves and socks to support the Partisans. Lea, Bernie and Sofia stayed in the barn. The Silberfarbs helped with farm chores. The family’s son was also in the Partisans. The whole town supported the resistance. Lea and the children stayed the winter. If company came to visit the family, Paula went to the barn.

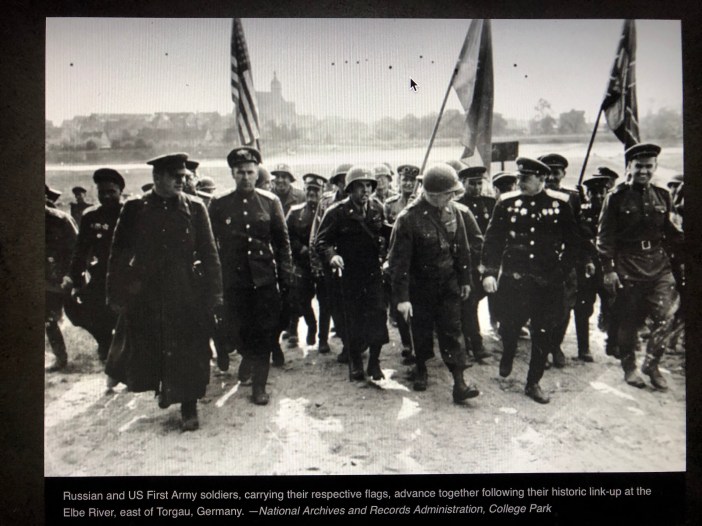

At this point, the Russians began to turn the tide of the war. The Silberfarbs were about 100 kilometers from Serniki when the area was liberated from the Germans, but the war was not yet over. They came upon the Russian army who shared canned goods and chocolates. “It was such a simcha (celebration)!” Paula exclaimed. They were in a bigger town, and though the bombing continued, they felt safer being with the army.

Sofia got typhus while they were in that town. Eventually Lea thought it was serious enough that she brought Sofia to the Russian infirmary. Sofia was cared for there. Each child, in turn, came down with typhus. Paula was admitted to the infirmary, as well. Bernie didn’t trust the doctors, and despite his illness, refused to go. He went so far as to jump out a window to avoid his mother’s efforts to get him to come with her. Lea worked in the infirmary, cleaning, emptying bedpans in return for the care of her children. After the children recovered, the army brought them to Pinsk. They sat on top of barrels of kerosene on the back of a truck for the ride.

When they got to Pinsk they shared a house with another family. Lea baked and sold bread to try and bring in some needed money, even though doing so was illegal under the Communist system. She was questioned by the NKVD, the secret police, numerous times.

One day at the market, as she was selling bread, Dmitrov Lacunyetz, the farmer who first hid the Silberfarbs, saw her. Neither of them could believe their eyes. They embraced, it was a tearful reunion. “Now I can die in peace,” he said. Throughout the war he wondered if he had really helped them. Lea shared some yeast and salt with him as a gesture of appreciation, though it was little compared to what he had done for them. He had risked his life.

Striving for normalcy, Paula started to go to school. The war finally ended in May of 1945 while the family was in Pinsk.

The Silberfarbs knew they couldn’t go back to Serniki. They wanted to go to Israel even though they had family in Brazil and Cuba. They wanted to be among Jews. Lea weighed their options. The first step was to go to a displaced persons camp, which was where transit arrangements could be made.

Next week: The Silberfarbs arrive at the DP camp and meet the Baksts and plan to emigrate.