I went on my first trip to Florida with Nana and Zada when I was in fifth grade. I’m not sure why I was chosen to go to Miami Beach with them – I was the fourth of the five grandchildren. It was my first time on a plane. I survived the flight without incident. I was proud of myself so I took the unused airsick bag as a souvenir and pasted it in my scrapbook.

It was dark when we emerged from the airport terminal in Miami and the three of us got into a checker cab to go to the hotel. The air outside was surprisingly soft. I had never seen a real palm tree before, but there they were: tall, narrow trunks lining the highway median, dark fronds etched against the violet sky. As I looked out the window of the cab, I could hear the music to the opening of the Jackie Gleason Show playing in my head and I wondered where the June Taylor dancers lived.

We stayed at the Sands Hotel. I shared a bed with Nana, while Zada had the other double bed. I was excited to go to the hotel pool and show them my swimming and diving skills. Unfortunately my shoulders got sun burned that first day and it was hard to swim after that. My skin was super sensitive and the tropical sun was a new and ferocious challenge.

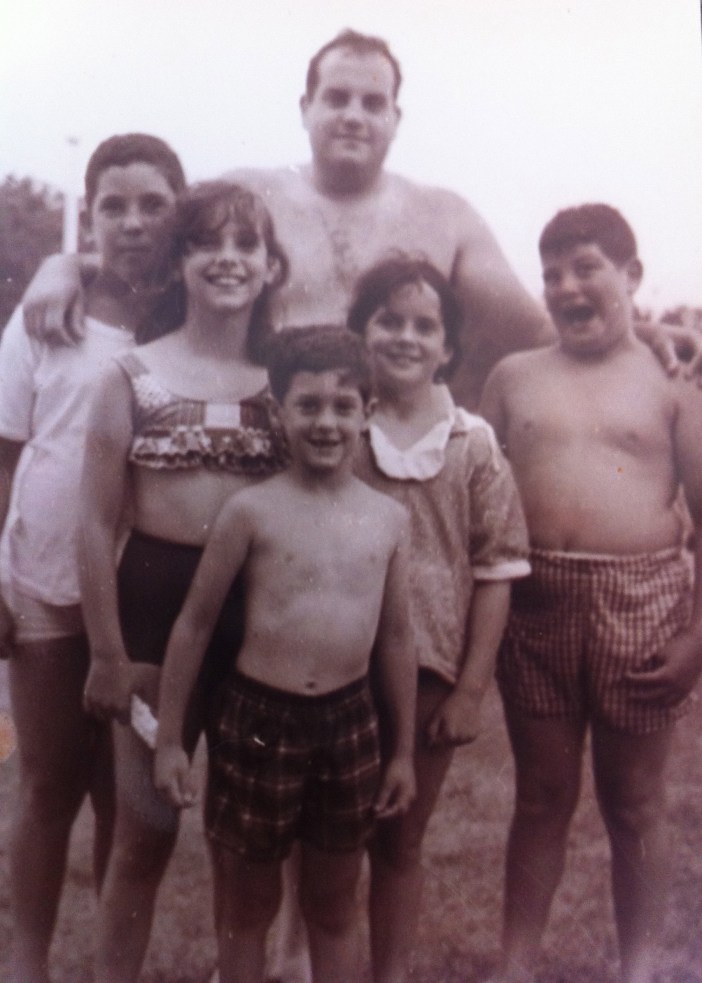

We spent some time visiting family that I didn’t know and friends of Nana and Zada’s who were also on vacation in Miami Beach. Nana and Zada tried to make me comfortable, but I got terribly homesick. I was embarrassed that I was teary-eyed while we visited with Red Rose (Nana’s friends had colorful names – Goldie, Sugar and multiple Roses).

It got better when Uncle Terry and Barbara, his girlfriend (a year later she became his wife), joined us. Though it was off-season, we went to Hialeah Race Track. Zada, who loved the horses, regaled us with stories about Citation as we looked at the statue of that beautiful animal.

We decided to cut my trip short and I went home with Terry and Barbara while Nana and Zada continued their vacation. I came home sun burnt and disappointed with myself. Miami Beach felt to me like another borough of New York City, just sun bleached and hot.

I went to Florida with my parents every couple of years after that to visit the elders. Zada moved to Century Village in West Palm Beach in 1973. My father’s parents moved to Century Village in Deerfield Beach in 1974. One year we took a miserable ride on Amtrak (we arrived 24 hours late!), another year we drove. Those trips, usually during our April break from school, didn’t feel like vacations. They felt obligatory. They could also be fraught.

Zada met and married Laura not long after he moved into Century Village. Laura was no match for our memories of Nana. Even if you took that comparison out of the equation, I failed to see (m)any redeeming qualities. It was later speculated that Zada didn’t want to be a burden on his family, he didn’t have much money, and Laura did, so he did what he thought he had to and married her.

Laura hailed from Massachusetts and prided herself on her fine manners. I think she was of the ‘children should be seen and not heard’ philosophy. During our first visit with her, Mark and I were sitting by the pool playing some kind of board game while our parents were chatting nearby with Zada and Laura. We could easily overhear Laura grumbling about how crowded the pool got when all the grandchildren descended from the north like locusts during these vacation breaks. My mother responded icily, “Don’t worry, these grandchildren won’t be here again!” This was not the only time that my Dad had to calm Mom’s rage at Laura.

Despite that threat, we did go back down to Florida in the years that followed. Although I think it came as a surprise to my parents, they ended up becoming snowbirds themselves about 15 years later when they retired from teaching. They bought a place in Boynton Beach in 1988, not far from West Palm where Zada still lived (he outlived Laura by a number of years).

As an adult, with my own children, we would make the pilgrimage to visit the elders, too. Gary’s parents also wintered in Florida. After renting in various places in the Fort Lauderdale area, they settled in Century Village in Pembroke Pines.

We wanted our children to see their grandparents so we visited at least once each winter. Both sets of grandparents did their best to make it enjoyable – and it was. Except for one thing. I couldn’t escape the feeling that retirement communities were depressing. My parents were as active as people could be: Mom participated in no less than two book clubs, the cinema club, she learned to paint, she made jewelry and ceramics and more. She said she felt like it was the summer camp she never got to go to growing up. My Dad played tennis twice a day, worked out, played cards and continued to read voraciously. They went out to dinner several times a week. They couldn’t have been happier.

Gary’s parents were also quite active. David sang in the choir, performed with the Yiddish theater group, and served on the Board of the synagogue. Paula and David went to shul, socialized with a group of fellow Holocaust survivors and played cards several nights a week. They went to the shows at the clubhouse, and they would use the treadmills in the fitness center. Occasionally they went out to dinner, more often Paula cooked or they ate at the cafe on the premises. They too enjoyed their life in Florida tremendously.

Yet, it depressed me – even before their health started to fail. We would drive into sun-drenched Century Village, the buildings clustered like barracks, the tennis courts empty, the golf course sparsely peopled, the man-made lake with no discernible use just a decorative fountain in the middle, and I would feel the sadness descend. The same thing would happen when we drove into Banyan Springs where my parents lived, though it was less cookie-cutter and usually there were people on the tennis courts. It still felt artificial.

It felt disconnected from the regular rhythm of life. I had experienced that feeling before. When I moved into Cayuga Hall in College in the Woods at SUNY-Binghamton as a freshman I struggled. College and dorm life were supposed to be the best time of my life. Instead I felt disconnected, as though real life was going on somewhere else. I enjoyed college much more once I moved off campus.

While some of the melancholy I felt when we visited our parents’ communities stemmed from the constant reminder of our mortality that is a fact of life there, I think it was really that I never did much like summer camp (or dorm life). Too much forced camaraderie, too much pressure to join activities, too much judging of and by others. Maybe we aren’t meant to live only among our own age group at any stage of life – or at least I’m not. Taken all together, memories, associations and my temperament, I’m thinking, when the time comes, retiring to New York City sounds about right.