Note: The following is a longer post than usual. For readers who have been following me from the beginning, some of the stories may be familiar. I have pieced together previous blog posts, along with new material, to create a more complete narrative of my relationship with Nana (my maternal grandmother). I am experimenting with different forms and approaches. Thanks, Leah, for your edits and suggestions. And, thanks Dan for your suggestion for the title. I look forward to feedback from any and all readers!

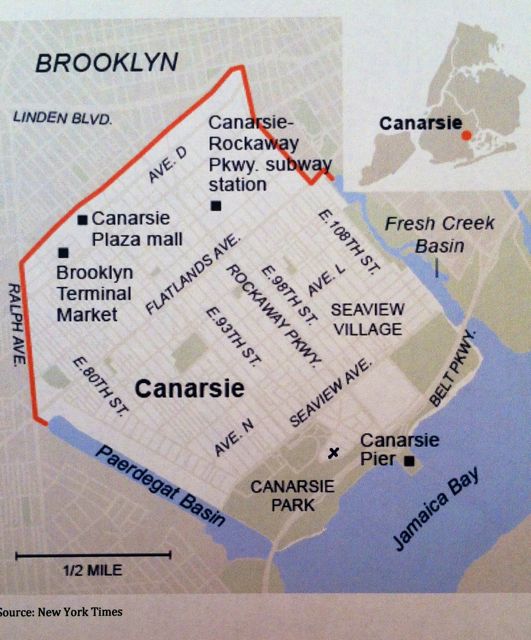

After renting various apartments in Brooklyn, my mom and dad took a leap of faith. They bought a new house in a new neighborhood, built on landfill, in Canarsie, Brooklyn. It was August of 1964, they were 30 and 31 respectively, and they were not at all sure that they could afford it on my Dad’s teacher’s salary.

The house, a two-family semi-attached brick and shingle structure, was on a street that had yet to be paved. Every time it rained the dirt road was awash in mud, puddles and rocks. Nana, Zada (my maternal grandparents) and my two uncles, who were teenagers at the time, took the apartment upstairs.

I started Kindergarten that fall and thus began a routine that would stretch over the next six years: go to school, visit upstairs with Nana, go back down for dinner with my parents and two brothers, do homework, go back up to watch tv with Nana, and, finally, go to bed.

Long before moving to Canarsie, Zada, in 1941 bought and managed Miller’s Bakery on Rochester Avenue in Crown Heights. Nana worked in the bakery alongside Zada and the family lived above the store. A master bread baker, Zada’s challah and rye bread were outstanding, in fact he had trucks delivering his product across the borough.

By 1962 the neighborhood in which Miller’s once thrived was changing. Zada thought that the new immigrants, mostly from the Caribbean, would buy his high-quality rye, pumpernickel and challah. But, they didn’t. He didn’t change his product and he didn’t follow his customers to Long Island either. So, for the second time in his life, he lost everything – he went bankrupt. At the age of 61 he went to work for a commercial bakery in Greenpoint, and moved his wife and two teenage sons to the upstairs apartment in our Canarsie home.

The door to Nana and Zada’s apartment was always unlocked. Each day when I came home from school, I dropped my stuff off in my bedroom, climbed the stairs, and let myself in. Though it was a two-family house, with separate apartments, I lived in it as if it was one.

Nana sat at a small, round marble table. The gold threads in the marble caught and reflected the light from the amber glass fixture suspended above it. The marble table top sat on a black cast iron pedestal. Both were unforgiving on misplaced elbows and knees.

“Hello, Sunshine,” her daily greeting to me as I opened the door. Nana’s arthritic hands were wrapped around a large teacup with steam rising. She lifted herself from her chair and shuffled across the yellow linoleum floor toward the refrigerator. I settled into a chair next to hers.

“Zada brought home a chocolate crème pie. Do you want a piece?” She was already removing the pie from the refrigerator shelf – she knew my answer. Zada often brought home surplus goods from the bakery – large black and white cookies, corn muffins or assorted pies, and I was always ready to indulge in a treat. As the refrigerator door swung closed, I saw Nana’s supply of insulin bottles lined up on the bottom shelf.

A small black and white television set sat on the table, tuned to the Dinah Shore show. The Mike Douglas Show came on shortly after. I ate my pie.

“Tell me about your day, Sunshine,” Nana asked.

“The usual. But, we have an assembly on Thursday and my class is putting on a little play. Maybe you could come?”

Nana sighed, “You know I’d love to, but my feet are hurting so much, there’s no way I could get there.”

My elementary school was not near the house, it was even a long walk to the bus.

“It’s okay, Nana. Maybe next time your feet will be better.”

We turned our attention back to the Mike Douglas show where the Rockettes were dancing. I adjusted the rabbit ear antenna so we’d get better reception.

“Lindale, bring me my aspirin,” Zada bellowed from the back bedroom. Another part of my daily ritual. Zada worked an early morning shift and was resting in bed while I visited with Nana.

“Coming!” I would get a glass of water, go into the bathroom and pour three aspirin from a huge bottle and bring it to him. Zada was propped up in bed, his long legs crossed at the ankles, wearing his sleeveless t-shirt, boxer shorts and horn-rimmed glasses, reading the Daily News. He took all three pills at once and washed them down with a gulp of water.

“Did you have the chocolate crème pie?” Zada asked.

“I did, it was delicious.”

“Good.” I took the glass back and returned to the kitchen, my job done.

The four o’clock sun streamed through the slats of the shutters in the window. I sat in my cocoon with Nana until my mom called me down for dinner.

On any given day, my visit with Nana might have included one of her friends from the old neighborhood. Like Nana and my mother, they relied on public transportation or car service because they didn’t drive. The nearest bus to our house left them with a long, windy walk across Seaview Park.

Alex, the tailor, who had one leg shorter than the other and wore a clunky orthopedic shoe, trudged across the park. Alex repaired the holes in my winter coat pockets by replacing them with a colorful, satin smooth fabric. I loved the orange and yellow cloth so much I wished I could wear the pockets on the outside.

Dora, Yetta and both Goldies made the trek to Canarsie, too. They climbed the stairs to Nana’s second floor home and settled in at the marble table, like I did.

Invariably they would bring a small trinket for me, a large chocolate coin wrapped in shiny foil, or a miniature stuffed animal. Nana smiled as they gave me my small treasure. After asking me what grade I was in and if I liked school, they went on to speak to each other as if I wasn’t there. I listened. Nana served tea and cake.

It seemed that Nana was a collector of lost souls. Some had physical problems, some would be considered spinsters, but no matter, they had a place at her table.

One day I took my usual place at the table and Nana shared an idea. Since my hair was a constant source of difficulty, she wanted me to try something different. A mixture of curls, waves and wiry frizz, my hair was entirely unmanageable. This was before the advent of the myriad of gels, creams, sprays and treatments that fill an aisle of CVS today. In the late ‘60s and early ‘70s, fashion required girls to wear their hair long and stick straight. I was in a state of war with mine – and my unruly hair was winning.

Combing my hair after washing it was a nightmare for both me and my mother, and anyone who was within earshot. My hair was such a jumble of knots that it was nearly impossible to endure the process. I would avoid the whole thing for as long as my mother would allow.

Nana came back from a session at the beauty parlor with her silver hair teased high, each hair sprayed into submission. Fortunately, that wasn’t what she had in mind for me, though that still might have been an improvement.

She explained that she spoke to another hairdresser at her salon about me. A new style had come into fashion, a shag, and they thought it could work. If I was interested, Nana would make me an appointment. I readily agreed.

After getting Mom’s consent, Zada drove Nana and me across Brooklyn to her beauty parlor. Nana was greeted with warm embraces and enthusiastic hellos. The smell of hairspray hung in the air. Most of the other patrons were Nana’s age.

A shag was a layered cut that allowed for curls. I watched as my hair was trimmed and styled. When it was done and I looked in the mirror, I breathed a sigh of relief and smiled. For the first time, my hair looked good! The other people in the beauty parlor even complimented me.

Zada picked us up and drove us back home. We were excited to show everyone. Nana walked in with me to see Mom’s reaction. Mom looked at me puzzled for a long minute, brow furrowed, and said, “I have to get used to it.” Her face said she didn’t like it. I burst into tears and ran to my bedroom. As I left I heard Nana say loudly, “Feige, you don’t know your ass from your elbow!”

I had never heard Nana use a curse word – ever. And, I never heard her say a cross word to my mother. I also had never heard that expression – it conjured up an image that shocked my eleven-year-old self. I didn’t know if I should laugh or cry – so I did both.

After a minute or two, Mom knocked on my bedroom door. “Nana’s right, Linda,” she said as she sat down next to me on my bed, gently stroking my back. “The cut looks great. I’m sorry for reacting that way. I was just surprised.”

“Ok,” I sniffled, “but I can’t believe Nana said that!”

“Well, she was upset with me. Don’t worry about it. Just enjoy the haircut.”

“You really think my hair looks okay?”

“I do. Go upstairs and let Nana know you’re feeling better.”

I did.

A few months later I climbed those same stairs to my grandparents’ apartment, knowing Nana was no longer there. I opened the door and found Zada sitting at the huge mahogany dining room table in his suit and tie. I crossed the room and went to sit with him to wait for everyone else to be ready to leave.

I was wearing the same dress, brown with white polka dots, cinched at the waist, that I wore a month earlier to my grandparents’ 40th wedding anniversary party. That party, with its frivolity and craziness (there had been a belly dancer, of all things!) seemed ages ago.

Zada looked at me and said, “Nana would be so happy to see you looking so pretty,” and his voice broke; he made a strangled sound. His shoulders heaved as he sobbed. I didn’t know what to do. I had never seen a grown man cry. I stood up and ran back down the stairs to my bedroom with the sounds of his grief following me. I didn’t know how to comfort him or myself.

Two days before, I awoke to the sound of Uncle Mike calling to my mom. “Feige, it’s mommy. She’s sick.” I heard his panicked voice in the hall outside my bedroom. Then I heard rustling sounds as my mom got out of bed, “I’m coming!” the slap of her slippers on the linoleum as she followed him upstairs. I pulled the covers over my head, trying to block out any more sounds.

I couldn’t help but hear the voices calling back and forth, the frantic phone calls being made.

Despite my growing fear, I got out of bed and slowly climbed the stairs to see what was going on. I stepped into Nana’s kitchen and my Dad stopped me.

“Nana would not want you to see her like this,” he said.

“Can I make her some tea?”

“Okay, why don’t you do that.”

I did and when it was ready, I wanted to bring it to her, but an ambulance was just arriving. I put the cup down on the marble kitchen table and retreated to our apartment. When I heard movement on the steps, I went back out into the hallway to try and see Nana. I couldn’t see her face, just her wavy white hair as they carried her to the ambulance.

All the adults piled into cars and followed the ambulance, siren wailing. It got very quiet in the house. Mark, my 14-year-old brother, an unbelievably heavy sleeper, had finally awoken in the tumult. I explained to him what was going on. Steven, my oldest brother, was away working at a resort hotel in New Jersey for the Easter/Passover holiday break from school.

Mark and I didn’t know what to do with ourselves. Mom and Dad had returned the night before from their first ever vacation without us. They went to Florida, while Nana and Zada watched us, and came back happy and tan. That happiness lasted only a few hours.

They also brought back souvenirs. With nothing to occupy us but our worry, Mark and I took our new alligator-shaped water guns and chased each other around outside – down the alley next to our house, into the backyard and back to the front. Squirting each other, we laughed to relieve the stress. Eventually we tired ourselves out, went back into the house and just waited.

After what seemed an interminable amount of time, though it was still afternoon, we heard people at the door. As the front door was being unlocked, I could see my Aunt Simma through the sidelight, tears streaming down her face. My Dad opened the door and came into the kitchen.

“Come, sit with me,” Dad said. He ushered Mark and me to the couch in the living room.

He took a deep breath. “Nana died,” he said quietly.

“What happened?” I asked, “How??”

“We don’t really know – maybe a burst blood vessel or blood clot.”

Mark immediately burst into tears. How did he do that? How did he understand it so quickly? I was numb. Dad patted Mark’s shoulder and put his hand on mine. “It’s okay to cry.”

I don’t know if he said that for Mark’s benefit or mine. I’m sure he offered words of comfort but I don’t remember what they were.

I learned a lot over the course of the next week. I learned about sitting shiva – the Jewish ritual surrounding death. I watched the mirrors in the house get covered with sheets; Mom, my aunt and two uncles and Zada each wore a black pin and ribbon to signify their loss; mourners used small hard stools instead of regular chairs. Each morning my uncles walked across the park to the nearest synagogue to say kadish. The house was filled with people, day and night; sometimes it felt like a party. Nana loved a party. It was strange – the happy chatter mixed with grief.

I learned that grown men do cry. Uncle Jack, Nana’s youngest brother, was sitting quietly one moment and then was overcome the next. I didn’t shed a tear, not then, not since. Nana was my comfort and heart, I felt a deep sadness, but tears would not come.

At the time, I thought Nana was old. She was 56. I am 58 as I write this.