One challenge in writing this blog is that it is disjointed. I’ve jumped around quite a bit, while still trying to follow some threads in a coherent way. I appreciate you readers taking the journey with me. Hopefully it hasn’t been too confusing!

In preparing to write this piece, I reread a bunch of posts to remind myself what I had covered. I don’t want to repeat myself, but I also want to make sure that each essay stands on its own. Please feel free to comment or message me if you have questions or if I’ve lost you! I welcome the feedback.

I’ve written about the ‘tense conversation’ (read here) Gary and I had about his applying to medical school. With all that went into the application, and all the pressure he felt, medical school presented quite a test – to Gary, to me and to our relationship.

Gary sailed through high school with minimal effort. He needed only a bit more energy to get through college. He began medical school not knowing how smart he was and without well-developed study skills. I think to some degree he had ‘impostor syndrome,’ he didn’t know if he belonged or deserved to be there.

Plus, he had his father’s hopes and dreams (and money for tuition!) riding on his success. Not too much pressure! Fortunately, Gary rose to the challenge. He not only met it, but he excelled. He set a brutal work pace for himself to achieve it.

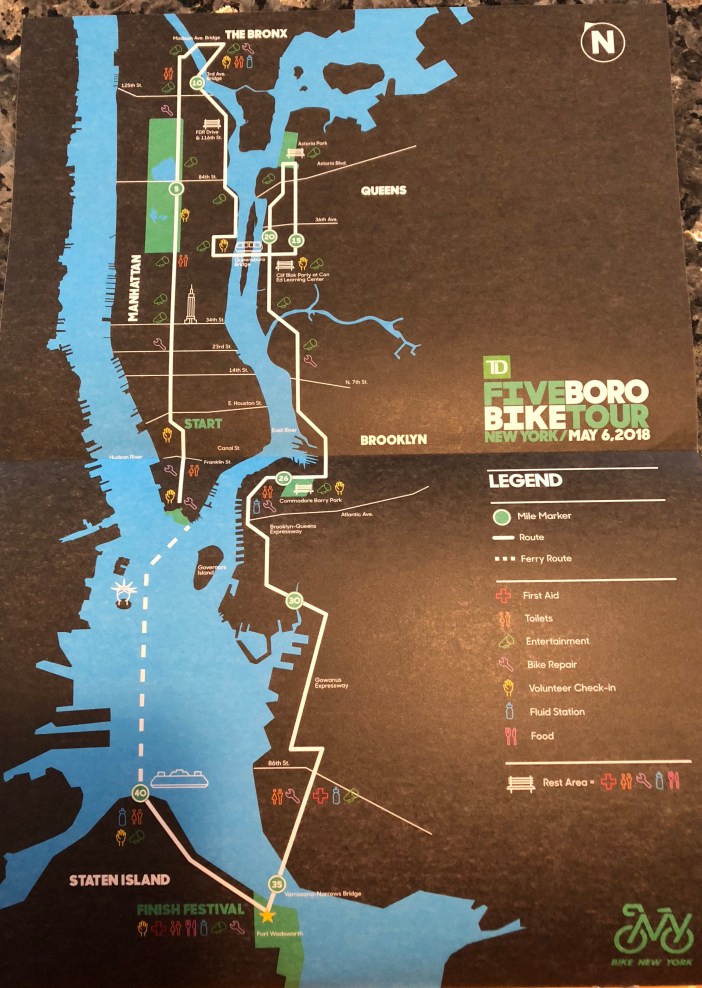

As I wrote previously, Gary and I drove a U-Haul from Queens to Pittsburgh in August of 1982. We parked the truck in front of Ruskin Hall in Oakland, the neighborhood which the University of Pittsburgh occupies, and got the keys and went up to the apartment.

Gary and his parents had traveled to Pittsburgh earlier in the summer to select the apartment, this was my first time seeing it. I was pleasantly surprised, and a bit overwhelmed. Tears welled as I looked at the high ceilings, huge windows, hardwood floors and spacious bedroom and living room. It reminded me of an upper west side of New York City pre-war apartment and I hadn’t expected something so nice. I couldn’t believe this was going to be Gary and my first home together. I wasn’t actually moving in with him at that point, I was going to join him later, but I knew it would be ours. I wanted to get at least six months in my new job before moving on, and Gary needed to get acclimated to medical school on his own. I knew I would be joining him in the not too distant future and I had no expectation that we would have such a nice apartment.

We moved the furniture in, which wasn’t much, but he had the essentials. We went to the nearest mall and bought some other items, including a phone. One of those new-fangled portable models that we plugged in and didn’t think anything more of it. After finding a grocery store and stocking the pantry and refrigerator with things he could easily prepare, I took a cab to the airport and flew home. I was sad to say goodbye, but fortunately airfare from New York to Pittsburgh was $29, thanks to PeopleExpress and US Air. We planned that I would visit once a month. We also planned to talk on the phone every few days and set our first phone date for Tuesday evening at 8:00, two days from then.

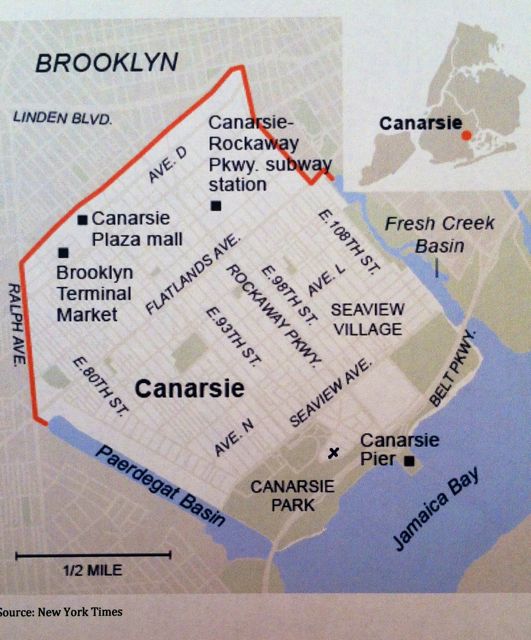

I went back to work on that Monday and pined for Gary. I couldn’t wait to talk to him. The appointed hour couldn’t come fast enough. At 7:59 on Tuesday evening, I picked up the phone in Canarsie and dialed Gary’s new number in Pittsburgh. The phone rang and rang. I counted 20 times. I hung up and dialed again and let it ring another 20 times. I was worried (was something wrong? Was he sick?). I was angry (how could he forget that we had a phone date?) I was confused (what should I do? There was no one to call to check on him). I kept trying. Eventually, he answered and he had a story to tell.

Gary was in the apartment, waiting for my call, keeping himself busy by refinishing a wooden desk that he had brought from home. He heard a chirping sound. Perplexed, he walked around the apartment trying to locate the source. It was a persistent, annoying sound and he wanted it to stop. He determined that it was coming from the smoke detector (also a new-fangled device in those days). He took the step ladder and tried to reach it to disconnect it (the downside of those high ceilings). No luck. The sound stopped, but then resumed. He got the broom and took the stick and pummeled the smoke detector. It fell to the floor, but the sound began again. It finally dawned on him that it wasn’t the smoke detector, but rather it was the new telephone. In the two days that he had been in the apartment it hadn’t rung once, so he had no idea what it sounded like. We were all used to the sound of the classic bell that our phones at home used when they jingled. This phone sounded more like a bird tweeting in a high pitched insistent tone. Meanwhile, back in Canarsie, I was in a panic. I was ready to be furious, until I heard his story. Then we started laughing. Though he had mangled the smoke detector, he was fine and would have the sound of that phone chirping imprinted on his brain forever.

It was a minor but amusing misunderstanding. We managed to communicate more successfully through that first semester. Gary wrote me a letter every day (I guess we shouldn’t be surprised that he writes the kids an email every day). I was a faithful correspondent, too. And, we had no further problems with the telephone. That isn’t to say that we didn’t have our struggles during his four years of med school, but more on that next time.